The Rebellious and Revolutionary Work of Designer Eiko Ishioka

Ishioka turned Japan's design scene upside down with a new approach to advertising, art direction, and costume design

For Eiko Ishioka, one of Japan’s most groundbreaking designers, creativity was an amorphous, fluid medium that she dipped into, gently molding materials into whatever form she was currently creating—a poster, an advertisement, or a costume. Born in 1938, Ishioka grew up in uptown Tokyo, raised by her father, a self-taught commercial graphic designer, and her mother, a housewife. After earning a degree in design at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, Ishioka began her career as a designer working in the advertisement industry, but throughout her wide-ranging career, she moved effortlessly between the roles of graphic designer, art director, and an Oscar-winning costume designer.

At 22, Ishioka joined the advertising department of cosmetics company Shiseido, at a time when the importance of design in Japan was beginning to be recognized. In a male-dominated team, she spent her days subverting the male gaze, and presenting a new, more confident image of a woman. Just when color photography was being introduced to graphic design, Ishioka created an advertisement for the brand’s “Honey Cake” soap, which featured a knife cutting through a luminous, jewel-like bar of soap. Moving away from Shiseido’s tradition of using Art Nouveau-style illustrations, Ishioka chose a photograph of the product that took centerstage. At a time when cosmetic products were presented as pristine and untarnished objects, her decision to put a knife through the soap accentuated it’s texture, creating a hyper-realistic image of the product; it was unlike anything Japan had seen before. In another advertisement for Shiseido’s “Beauty Cake” and “Sun Oil” products, Ishioka showcased model Bibari Maeda floating in blue waters or stretched across a sun kissed beach, shattering the conventional image of a beautiful woman as “gracefully neat and doll-like,” as Ishioka would later describe. The visuals were bold and sensational, and the posters were such a hit, people began stealing them from the streets where they hung.

Ishioka’s impulse to challenge what was perceived as “traditionally Japanese” developed during her childhood, when she was introduced to the beauty of both the East and the West. Her early life in Tokyo was informed by her parents’ love for French restaurants and American movies. At the start of World War II, her family moved to the countryside giving Ishioka a glimpse of a more bucolic, traditional Japanese life. Years later, when she began her career, this in-betweenness of her identity fueled her drive to forge a visual bridge between the East and the West, and immediately question the definition of the ideal woman, as portrayed in Japanese popular culture.

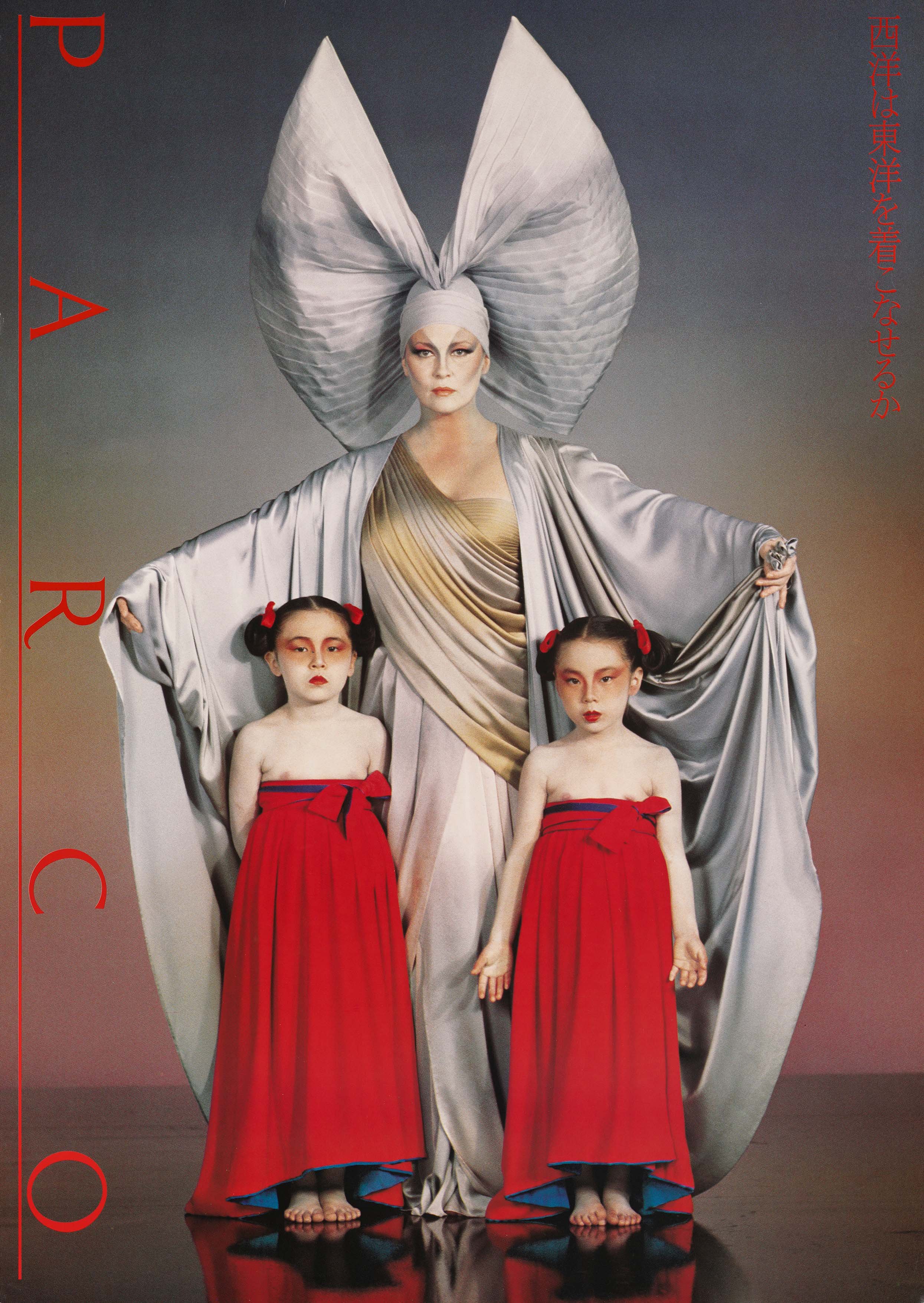

Ishioka used her knowledge of modern design to imbue her work with eroticism and physicality, says Tomoko Yabumae, curator of the ‘Eiko Ishioka: Blood, Sweat, and Tears—A Life of Design’ an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo; a virtual archive of the exhibition will be released later this month. “She presented a new image of a woman, a woman who looked back at the world with a strong gaze, rather than a woman who was ‘seen’ in cosmetics advertisements,” Yabumae says. This sensibility carried over into her work for Parco, a shopping complex that was just getting its start in the 1970s. Working with a range of talent—from Faye Dunaway, to models from India, Morocco and Africa, who presented very different definitions of female beauty—Ishioka introduced her ensemble of women as strong and confident, staring intently at the camera, as seen in her advertisements, “This is a Picture for Parco” and “The Nightingale Sings for No One but Herself.”

“(In Japan) a woman can’t look too strong. Strong eyes mean strong confidence,” Ishioka said in an interview with Ingrid Sischy for Artforum Magazine in 1984, when describing her intent for “The Nightingale Sings for No One but Herself,” an advertisement she created for Parco in 1976. “The average Japanese woman can’t look people in the eye. She has to be behind a man, passive for a man. This is the reason women don’t look with strong eyes toward a person. I wanted to tell Japanese women, please think with strong confidence in life, and please look.”

Ishioka’s campaigns were a clarion call for Japanese women at the time. With tag lines like “Girls Be Ambitious!,” “Women! Turn Off Your TV Sets! Women! Close Your Magazines!” and “Don’t Stare at the Nude; Be Naked,” her defiantly anti-product ads asked women to reconsider the prevalent culture and challenge their existing perceptions. “Through Parco’s advertisements, Ishioka conveyed the message that fashion is a means to live with independence,” says Yabumae. “In conjunction with the image of her advertisements, Parco grew to become one of the centers that led women to live mature lives, as an introducer of not only fashion, but also diverse cultures such as theater and music.”

Through her early works as an art director, Ishioka was also exploring some of her quieter passions: her penchant for treating the body as a canvas, as seen in her anti-war poster “Power Now” that features bodies folded in forms “reminiscent of clenched fists that can be regarded as a symbol of anger.” Underscoring all her work, was also her love of a very specific shade of red, almost verging on maroon, that to her signified elegance, intelligence and perhaps something dangerous or forbidden. This color appeared in her ad for Parco “Can West Wear East?,” which featured Ishioka’s nieces in red dresses that slightly reveal their nipples, tucked under the wings of Faye Dunaway’s kimono. It would continue to show up in Ishioka’s work, including in her Oscar-winning costumes for the 1992 film Dracula.

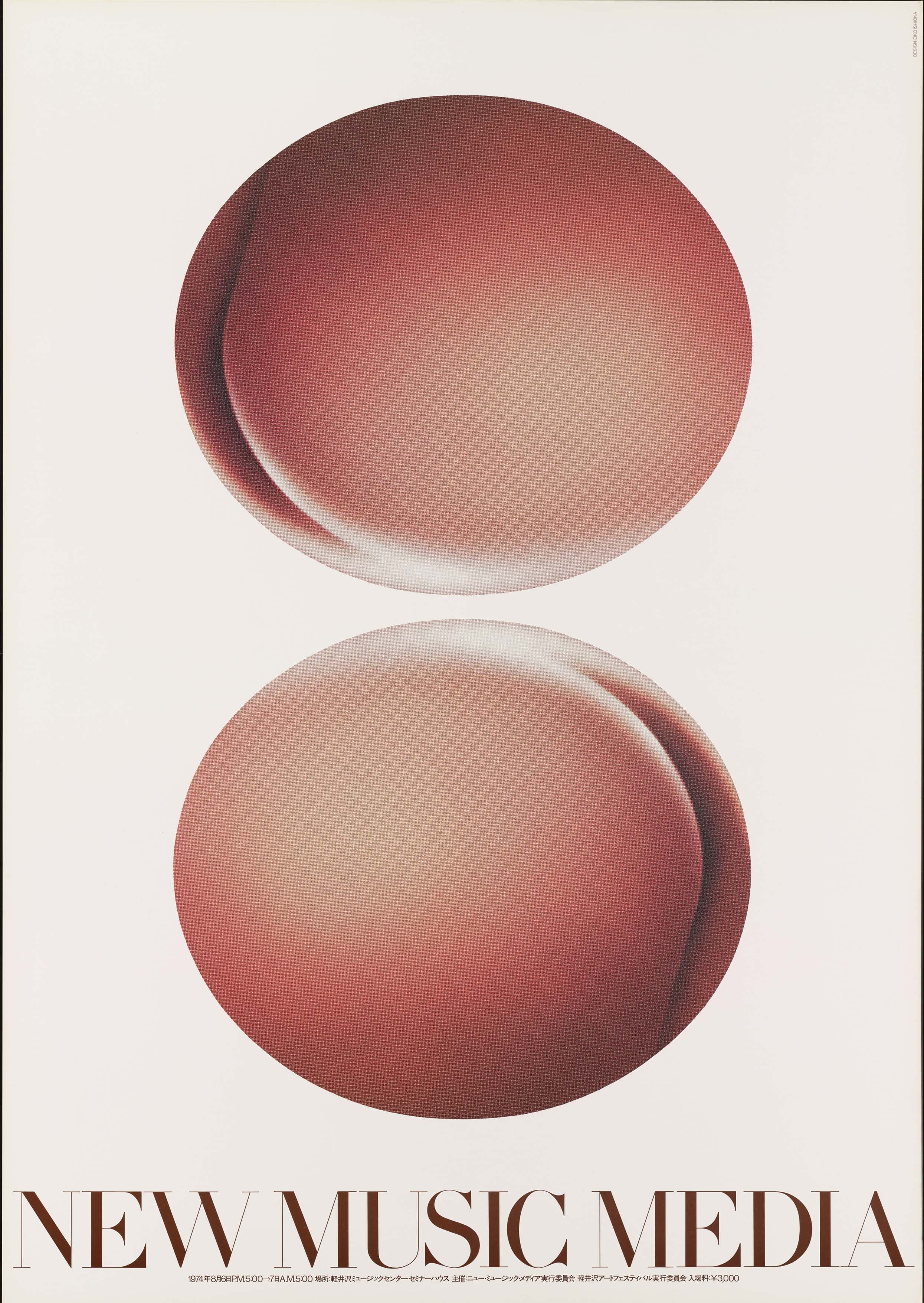

By the time she moved on from her role at Parco in 1983, Ishioka had already shaken up the design world in Japan and grown into her reputation as a provocateur, but she was only getting started. Her work for publishing company Kadokawa Shoten reinvented the image of paperback books through redesigned covers of famous books that used photography in a modern way. “The covers of these paperbacks were each printed in a different design in full-color, replacing former ones with vividly eye-catching creations, complete with a belly-band featuring a campaign copy,” notes Yabumae. “Her designs removed the antiqueness associated with the genre of literature, creating a strong and impressionable image of paperback books as a fashionable medium for young people.”

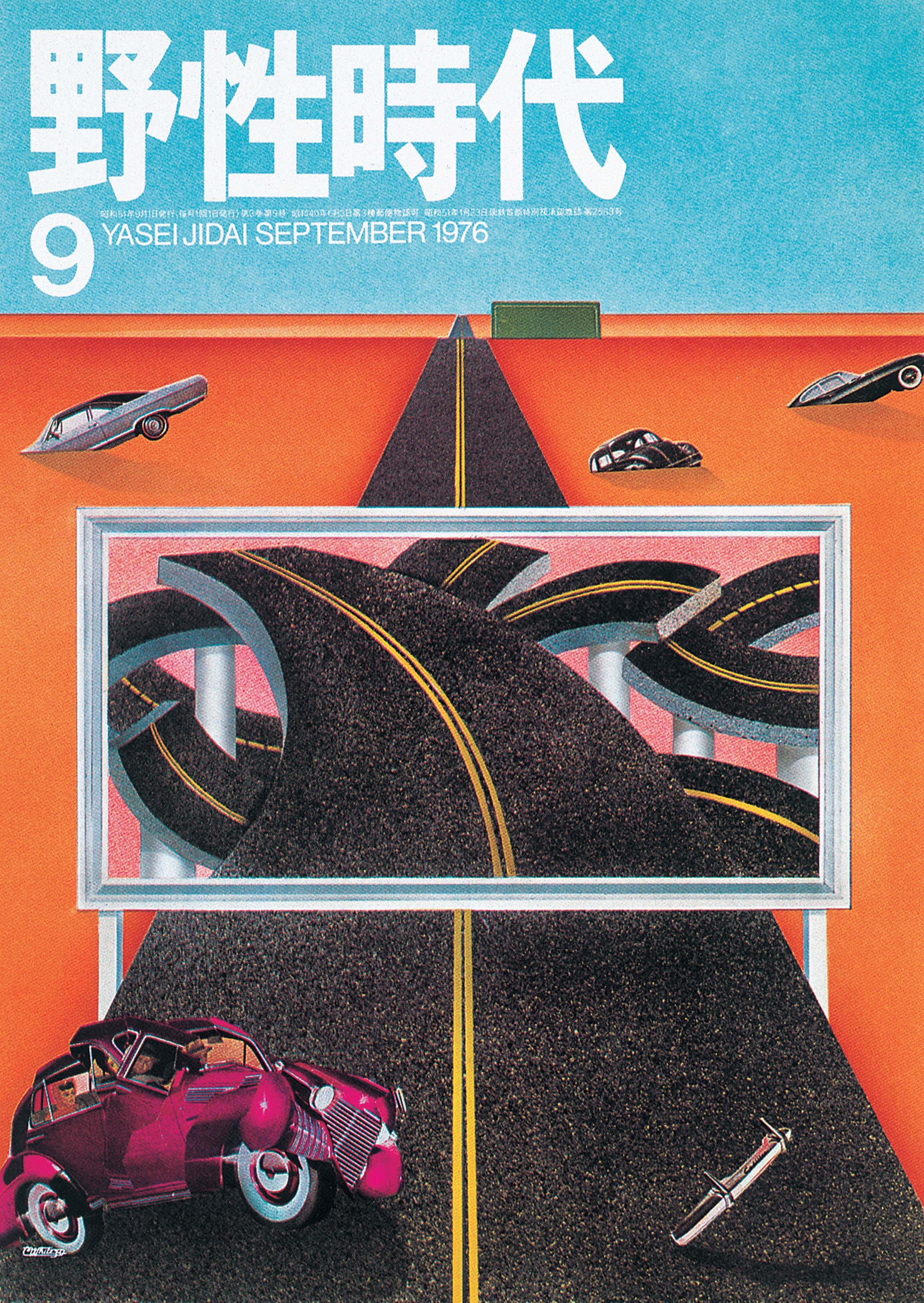

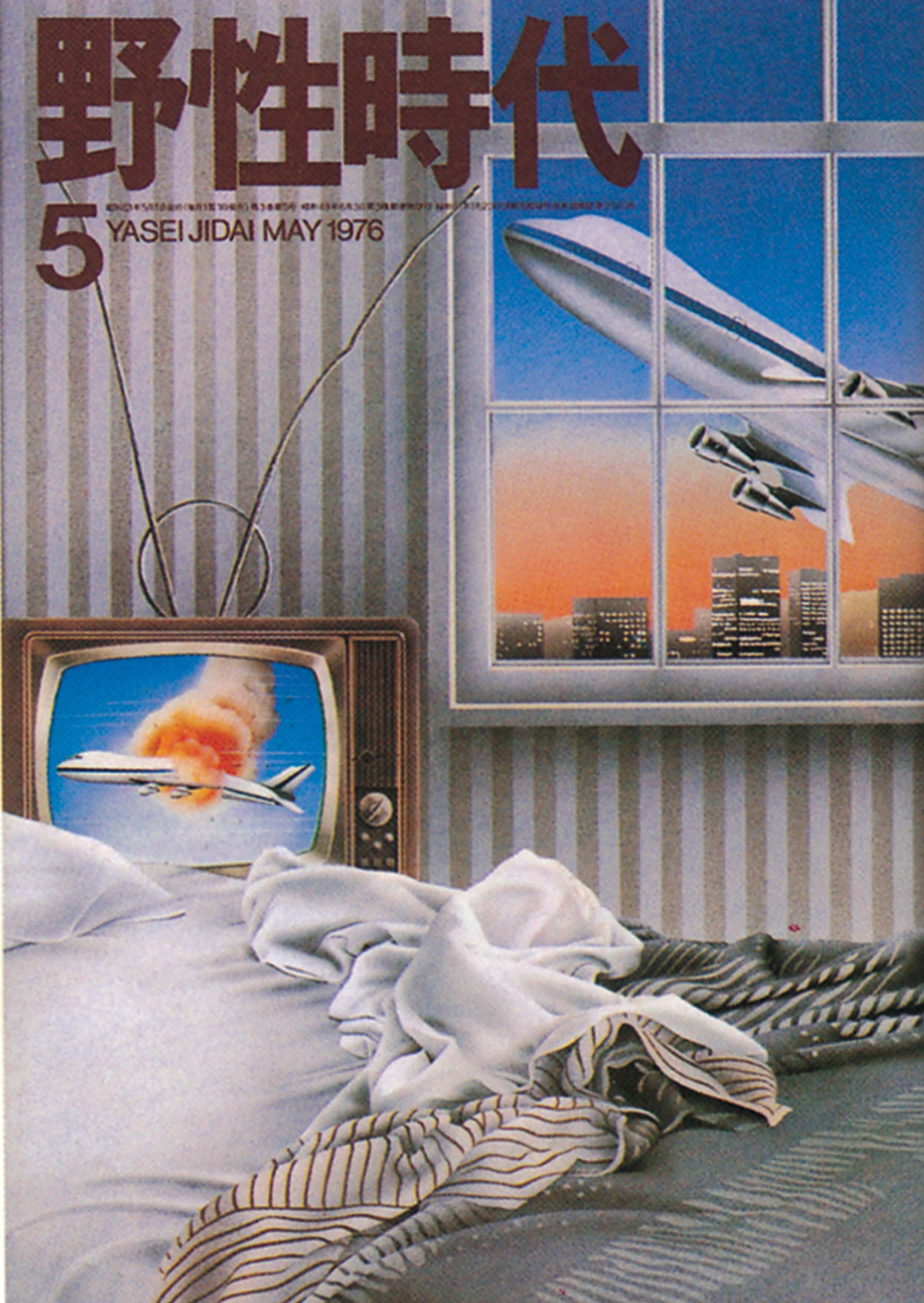

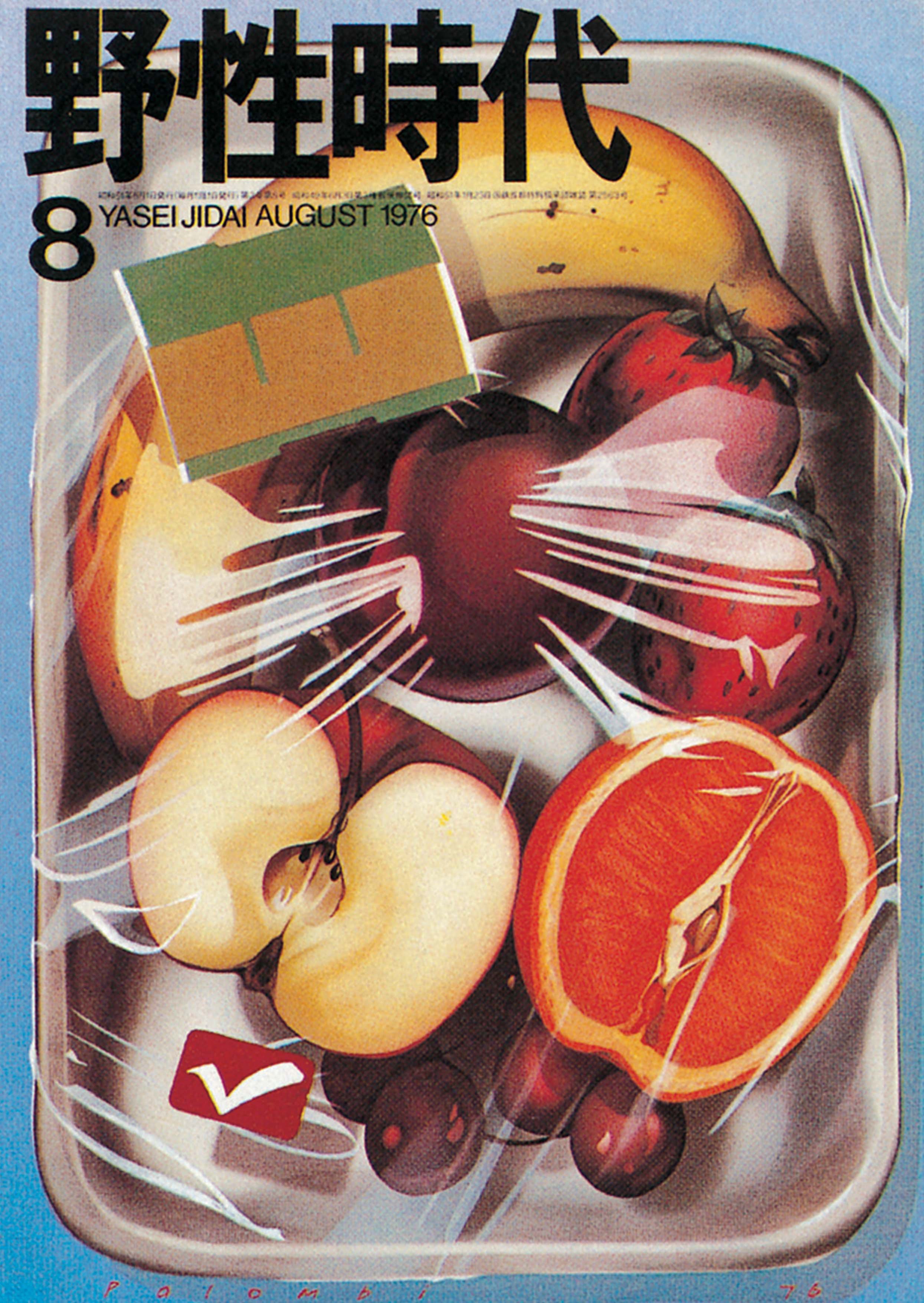

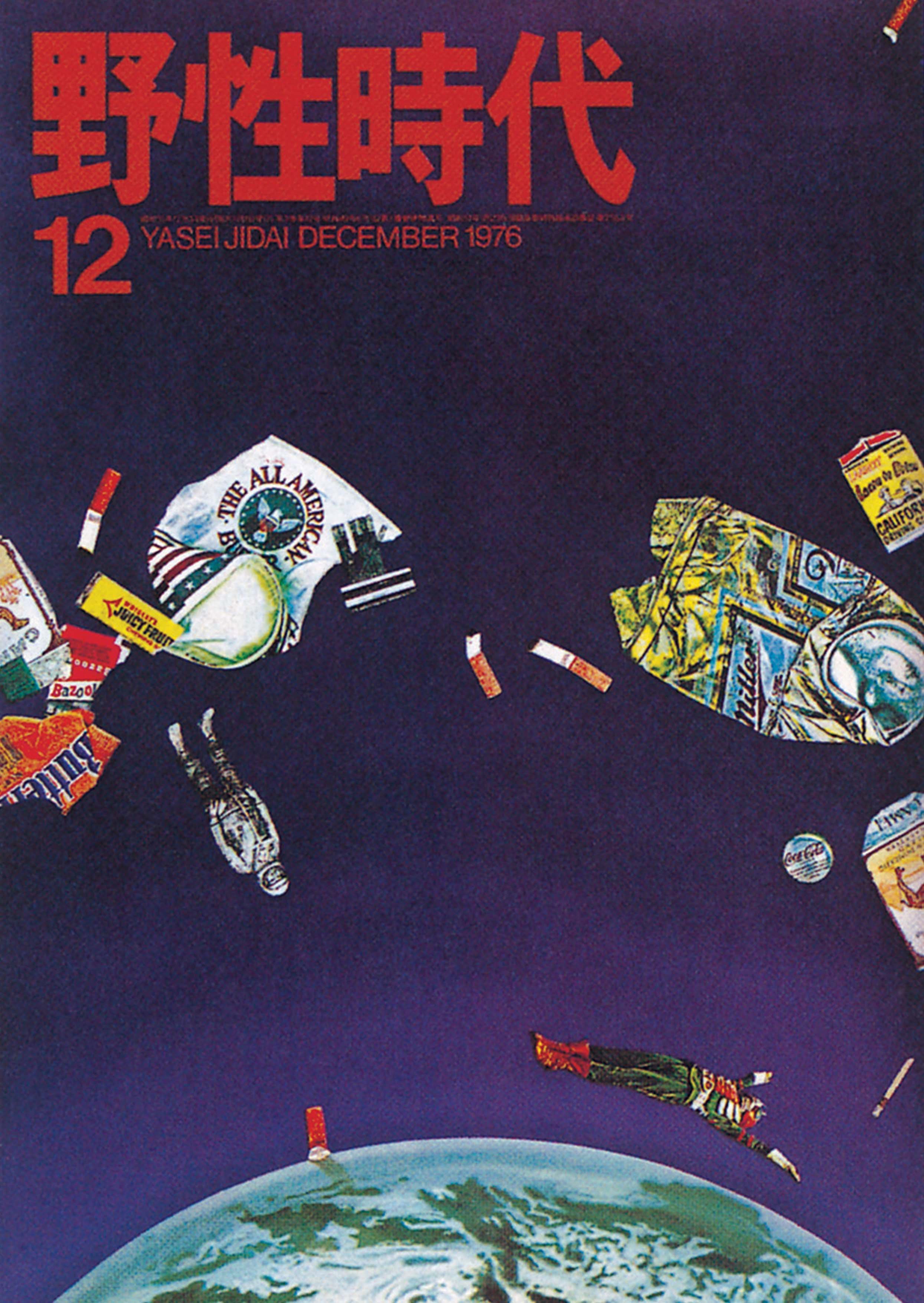

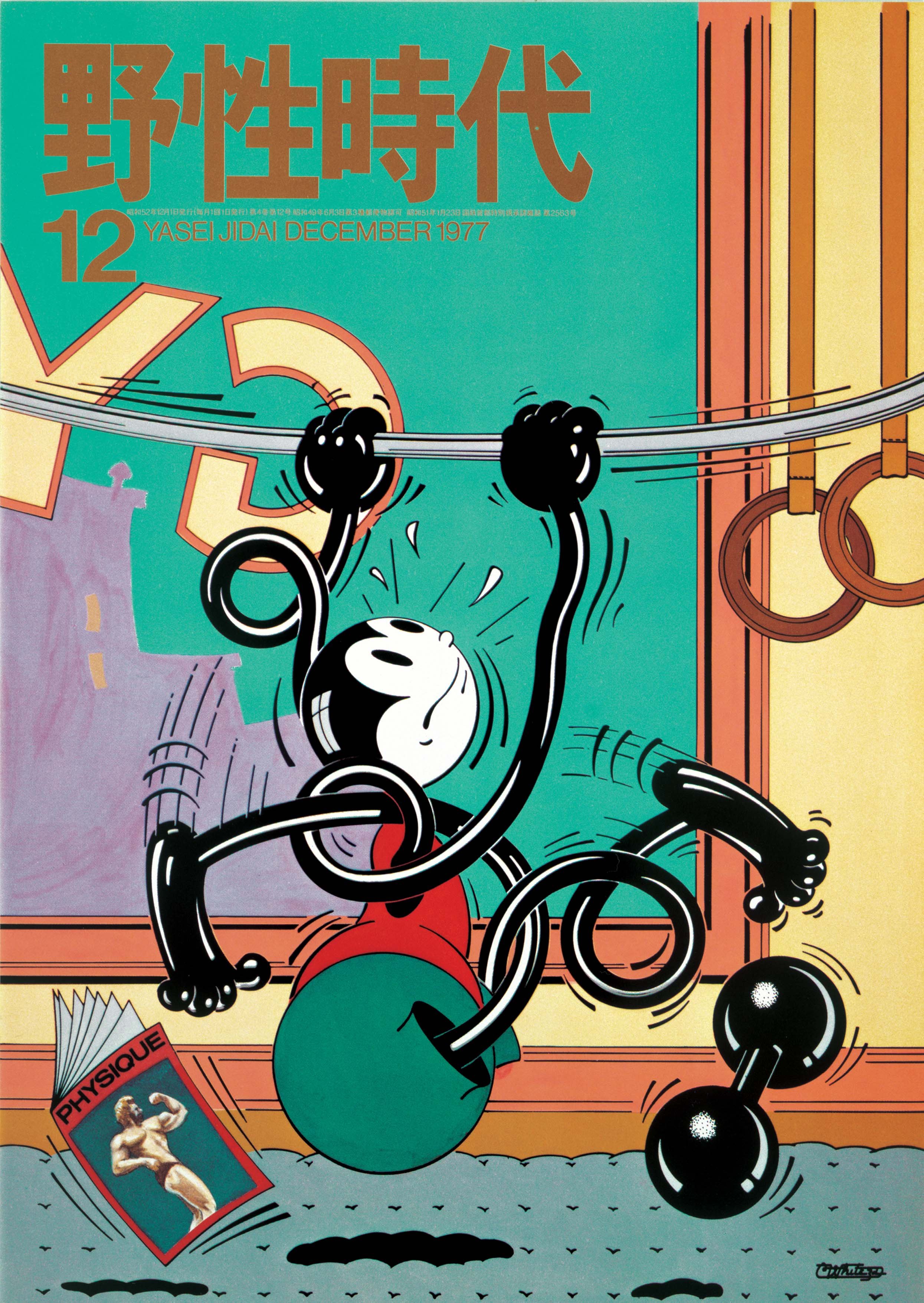

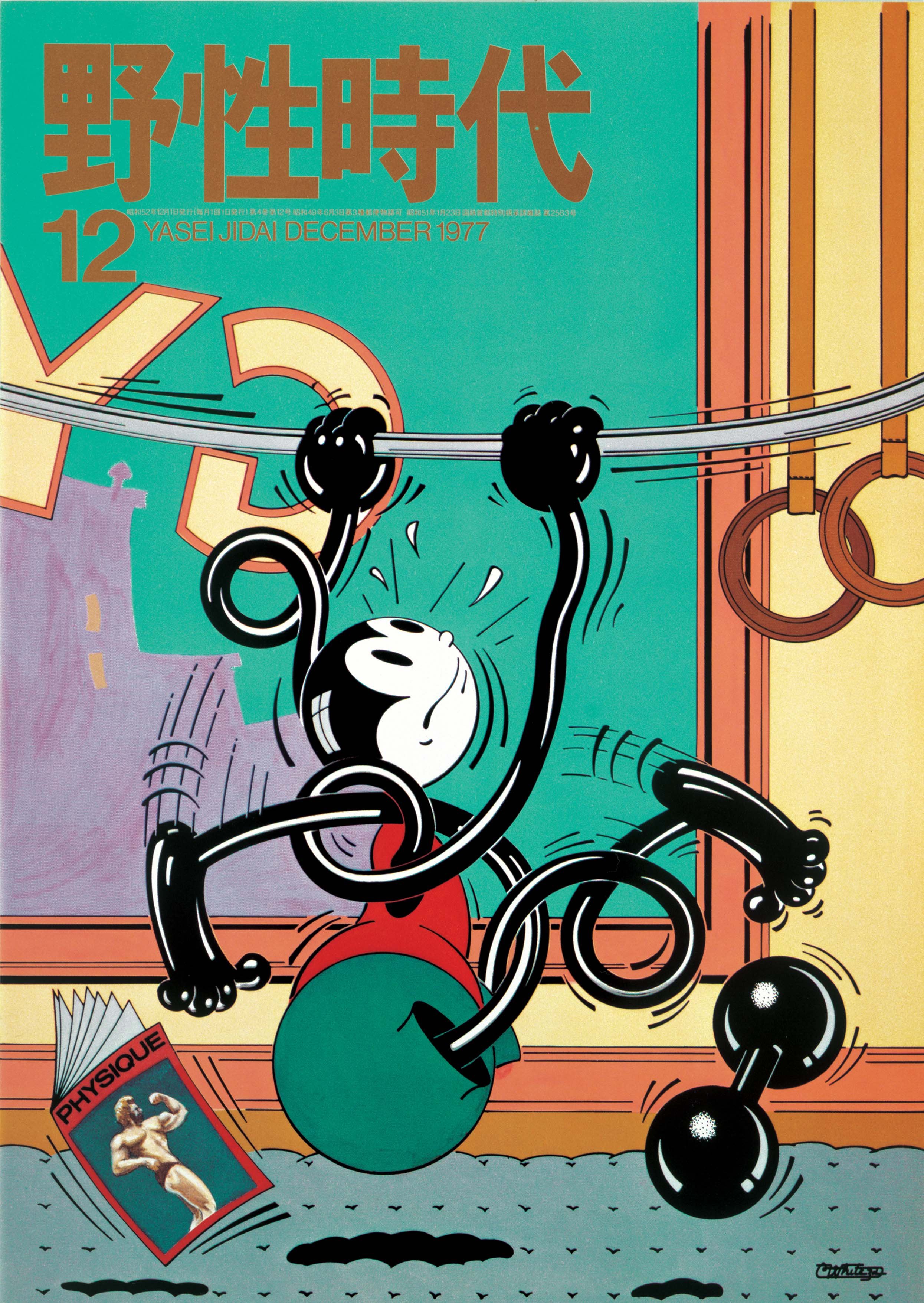

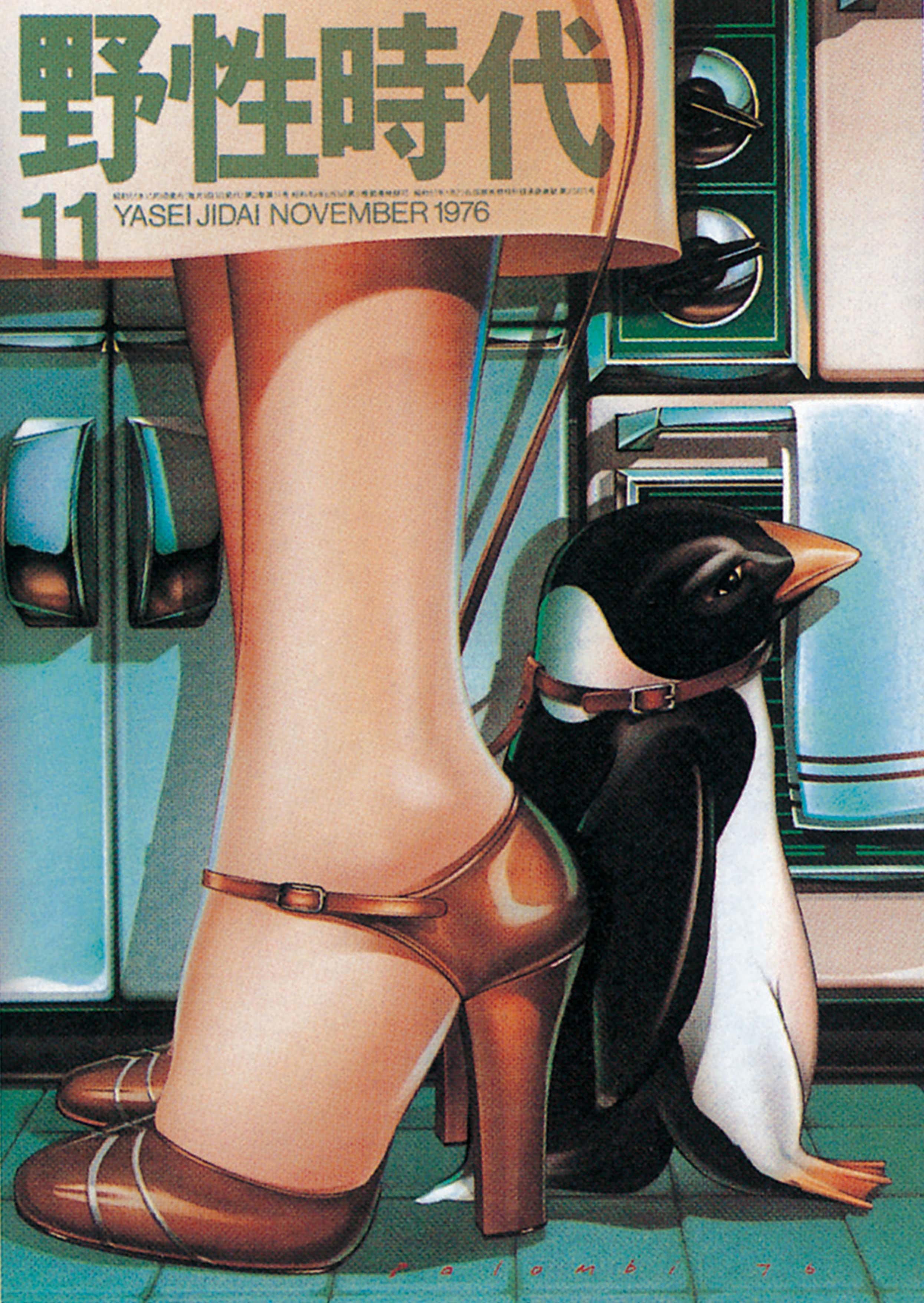

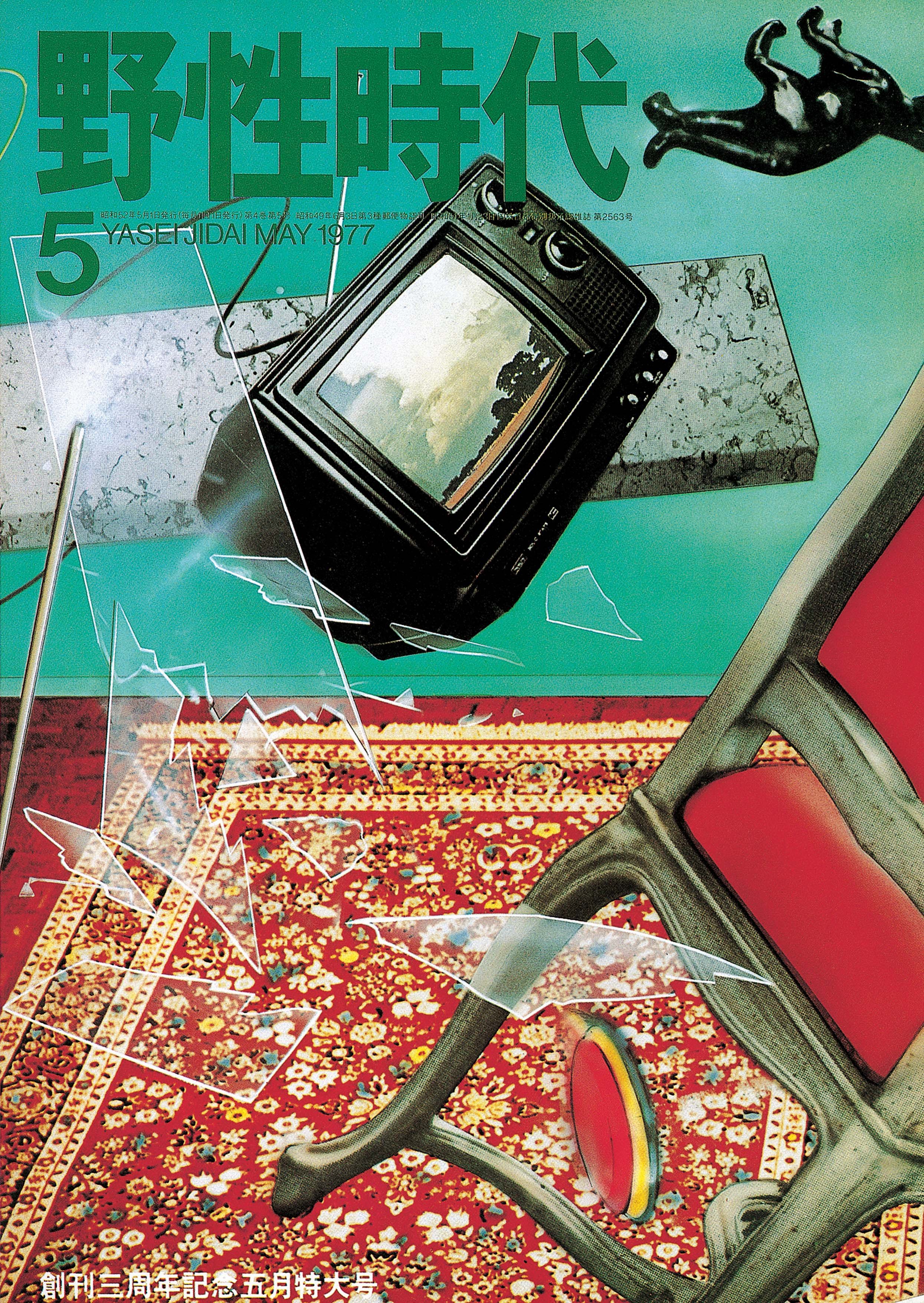

At the time in Japan, it was unusual for an art director to be involved in the making of literary magazines, which relied solely on printed text, a notion Ishioka defied yet again with her provocative covers for the Yasei Jidai (Wild Age) magazine, that explored the contemporary problems faced by urbanites. On one cover, a confetti of pills scattered across a blue face; on another, the light reflected off taut cellophane that covered a plate of cut fruit. Her covers were only one aspect of her work for the magazine, which also involved logotype design, layout, and the planning and production of its special features. “Her work was driven by collaborations. She commissioned popular illustrators such as Charles E. White III, and worked with typographers and photographers throughout her career,” says Yabumae, noting that her works, despite being a collaborative effort, ultimately looked and sounded like “the voice of a single human being.” “For me the media is my canvas and a talented collaborator, a photographer for example, is my paint,” Ishioka once said.

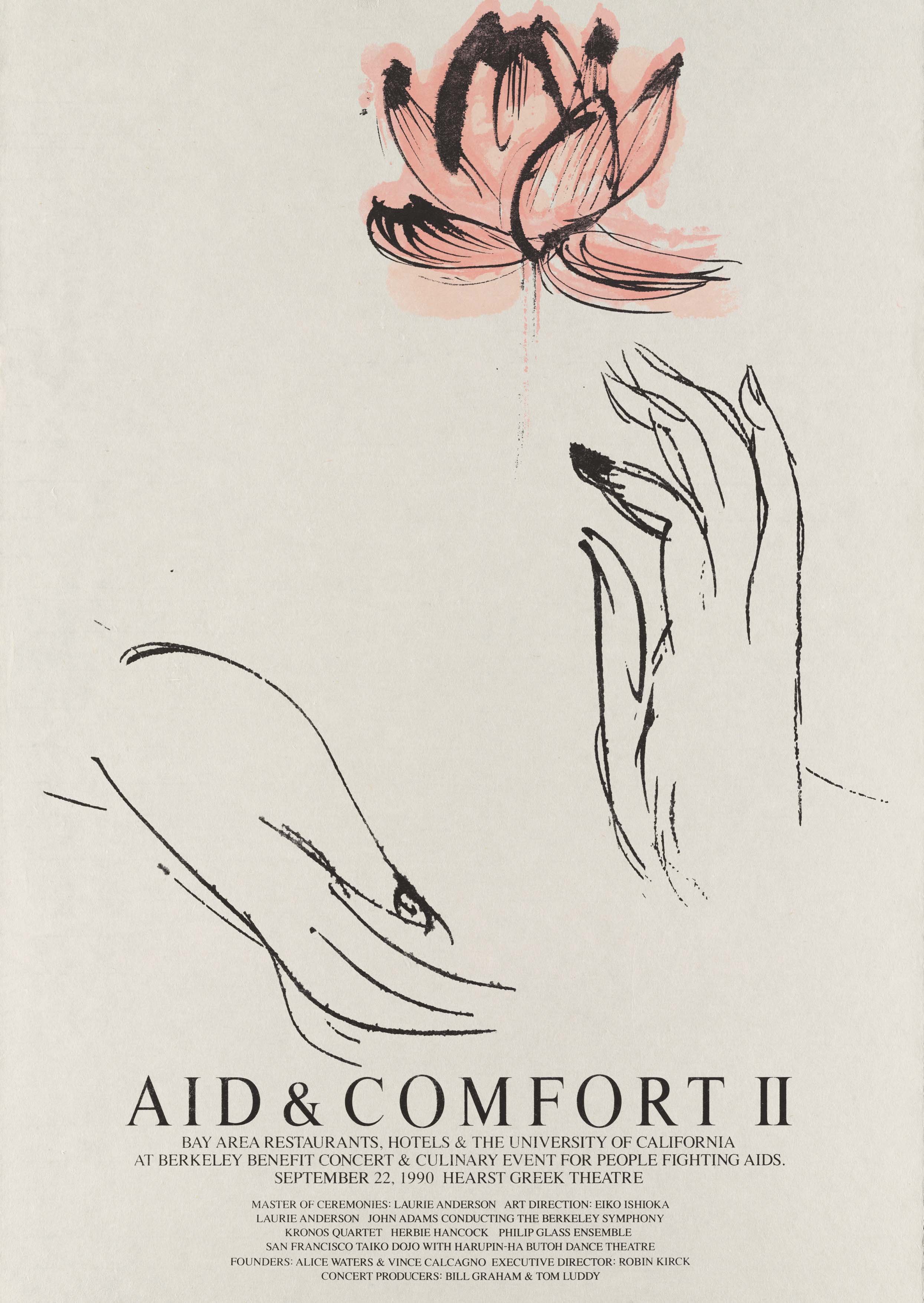

Ishioka was driven by creative variety. She went on to win a Grammy in 1987 for the album packaging of Miles Davis’ Tutu; she created otherworldly costumes for films by Francis Ford Coppola; she directed the video for Björk’s “Cocoon;” and designed the performers’ costumes for the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics in 2008. Ishioka loved her work until the very end of her life; months before her death in 2012, she finished working on costumes for Tarsem Singh’s film “Mirror Mirror.” With an oeuvre that’s almost impossible to summarize, Ishioka inspired the world, and turned the world into her inspiration. “Everywhere on Earth is my studio,” she said. “Everything on Earth is my material.”

To learn more about the release of the digital archive of ‘Eiko Ishioka: Blood, Sweat, and Tears—A Life of Design’ later this month, keep an eye here.

This article was originally published on Eye on Design.